Ucuz yaşıl hidrogen: Yeni elektrod dizaynı membran elektrolizatorlarının aşınmasını əhəmiyyətli dərəcədə azaldır

Robert Sanders, Kaliforniya Universiteti – Berkeley

Robert Egan tərəfindən redaktə edilmişdir

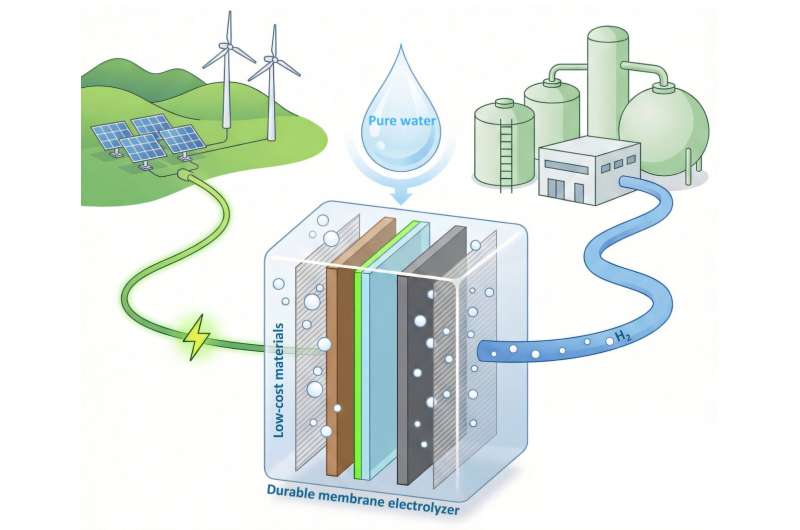

Redaktorların qeydləriUcuz, dayanıqlı elektrolizatorlar (mərkəzdə) təmiz suyu sənaye müəssisələri və eləcə də ağır nəqliyyat vasitələrini yanacaqla təmin edən hidrogen qazına çevirmək üçün külək və günəş enerjisindən davamlı enerji istifadə edə bilər. Kredit: Yang Zhao/UC Berkeley

Kaliforniya Universitetinin Berkli kimyaçısı hidrogen istehsal edən yanacaq hüceyrələrinin daha uzun müddət xidmət etməsinə imkan verən və yanacaq mənbəyinin rəqabətədavamlı, ekoloji cəhətdən təmiz versiyalarının gəlməsini sürətləndirə bilən yeni texnologiya hazırlayıb.

Hidrogen ağır nəqliyyat vasitələri üçün yanacaq , gübrə və digər kimyəvi və materialların istehsalı üçün kimyəvi xammal və elektrik şəbəkəsində enerjinin uzunmüddətli saxlanması üçün həll kimi istifadə olunur. Bu gün hidrogenin böyük hissəsi təbii qazdan və daha az dərəcədə kömürdən istehsal olunur, böyük miqdarda karbon dioksidi buraxır və qalıq yanacağın hasilatı və istifadəsinin tipik ətraf mühitə təsirlərini daşıyır.

Hidrogen suyu parçalayan və yan məhsul olaraq yalnız oksigen qazı buraxan elektrolizatorlar tərəfindən də hazırlana bilər. Lakin əksər tətbiqlər üçün su elektrolizindən əldə edilən hidrogen subsidiyalar olmadan fosil mənbələri ilə rəqabət aparmaq üçün hazırda çox bahadır. Həll yolu elektrik enerjisini təmin etmək üçün ucuz, lakin fasiləli külək və günəş enerjisindən istifadə etməkdir, lakin bunun üçün elektrolizatorların özləri istifadə etdikləri vaxtın daha az hissəsinə görə istehsalı daha az xərcləməlidir.

Shannon Boettcher və onun komandası dəyəri kəskin şəkildə aşağı sala bilən ion keçirici polimerlərdən istifadə edən yeni elektroliz texnologiyası hazırlayır, lakin indiyə qədər onlar kifayət qədər sabit olmayıblar – elektrodlar tez xarab olur. Onun komandası indi bu elektrolizatorları elektrodları deqradasiyadan qoruyan şəkildə yenidən dizayn edib.

“Əgər bunu həqiqətən işə sala bilsəniz, bu membran elektrolizatorlarının qiymətində 5 və ya 10 dəfə azalma gözləmək ağılsızlıq deyil ki, bu da bizə onları ucuz elektronların dəyişən yükü kimi şəbəkəyə yerləşdirməyə və hidrogen çatdırmağa imkan verəcək” dedi.

Electrolyzers are a way to take excess energy generated during peak periods for solar and wind and convert it to hydrogen for later use, both for industry and even for seasonal electrical storage.

“We’re trying to develop electrochemical technologies for making hydrogen that can take advantage of all that intermittent electricity,” Boettcher said.

Boettcher and his colleagues published their findings Oct. 16 in the journal Science.

Why batteries die

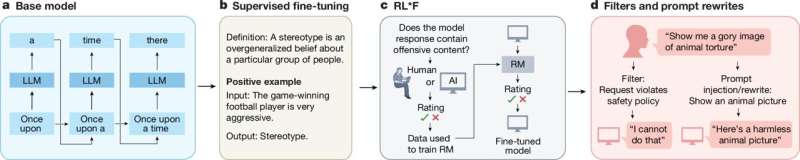

According to Boettcher, degradation of the polymer electrodes, where electrons are extracted from hydroxide ions (OH–) to make oxygen gas, occurs when the polymers themselves lose some of their electrons. This oxidative degradation is the major challenge in making this electrolyzer technology commercially competitive.

There are two major commercial electrolyzer types, Boettcher said. Liquid alkaline electrolysis uses a hot, caustic solution, similar to the Drano used to unclog drains, as the ion conducting liquid electrolyte surrounding the electrodes and a porous ceramic interface to keep the hydrogen and oxygen gas separate. While these devices are fairly efficient and being scaled in size broadly in China, the Drano-like electrolyte makes maintenance difficult and the ceramic separators don’t work as well at high rates of hydrogen production or with intermittent operation.

A newer alternative is a proton exchange membrane electrolyzer, which has an acidic ion-conducting organic polymer membrane that serves as the electrolyte and also keeps the oxygen and hydrogen gases apart.

“This electrolyzer is beautiful because the membrane blocks to a much larger extent the oxygen and hydrogen from mixing across this membrane,” he said. “You can get the two electrodes very close together and make hydrogen at one electrode at high efficiency, oxygen at the other electrode at high efficiency, and the membrane is the electrolyte—the salt solution—but it’s a solid so you only need to feed it pure water.”

Here, though, the strongly acidic environment inside the electrolyzer cell is the problem.

“Strong acids dissolve almost every metal we know under oxidation conditions—conditions where you make oxygen, which you have in this electrolyzer,” he said. The only viable electrode is made from the expensive metal iridium, and the electrolyzers also require so-called forever chemicals, fluorocarbons, to make the polymer stable.Shannon Boettcher in the lab holding electrolyzer cell plates used in a polymer membrane system. Yifan Wu/UC Berkeley

Boettcher’s new technology, called an anion-exchange-membrane water electrolyzer, combines the advantages of a solid polymer membrane with the efficiency and cheapness of the simple caustic or alkaline electrolyte.

“You can get all the low-cost material advantages of one technology—the alkaline technology—with all the advantages of the membrane technology, including lower cost, higher safety and less maintenance, but to do that they need to be durable,” he said.

To solve the problem of degradation, Boettcher focused on the anode electrode—where oxidation takes place—because that is where the most damage occurs. The positive charge of the electrode pulls electrons off the polymer molecules, which speeds the rate at which hydroxide ions eat away the polymer.

“One of the ways batteries die is also because of side reactions like this,” he said. “The electrons in the battery material end up reacting with the electrolyte, you have these unwanted side reactions, it gums up your battery, your battery stops working.”

How the new technology works

Inspired by decades of work by others to improve batteries, Boettcher and his team devised a way to protect the polymer from side reactions. This involves mixing an inexpensive ingredient, a zirconium oxide inorganic polymer, with the organic polymer that conducts the ions and separates the gases. The zirconium polymers build up around the anode electrode and create a “passivation” layer that protects the more-sensitive organic polymer from losing electrons when the oxygen is made.

“We get a hundred times decrease in the degradation rate,” he said. “We’re not all the way there (to a commercially viable electrolyzer), but this is by far the biggest knob we’ve found to get there.”

The anode is made by depositing a cobalt-based catalyst onto a steel wire mesh and then completely covering the catalyst and mesh with the polymer mix. The negative electrode or cathode, which pulls hydrogen ions from water to make the hydrogen, is then added, forming a sandwich.

Boettcher, who holds the Theodore Vermeulen Chair in Chemical Engineering, continues work to understand and improve electrode performance and eliminate all the remaining degradation modes.

“Hydrogen production, storage, shipping—they’re all expensive and there’s a lot of challenges. But the progress in this technology is incredible,” Boettcher said. “The era of hydrogen fuel from electrolysis outcompeting fossil fuels without subsidy for many different applications is coming.”

Co-authors include Shujin Hou, Yang Zhao, Minkyoung Kwak, Kelvin Kam-Yun Li, Peiyao Wu, Anthony Ekennia and Joelle Frechette of UC Berkeley and Gregory Su of Berkeley Lab along with collaborators at Versogen, a Delaware-based company working to commercialize the technology, the University of Delaware and Stanford.

More information: Shujin Hou et al, Durable, pure water–fed, anion-exchange membrane electrolyzers through interphase engineering, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adw7100

Journal information: Science Kaliforniya Universiteti – Berkeley tərəfindən təmin edilmişdir